If they successfully agree to new terms, then this could inspire copycat efforts– including those on false pretexts – for pressuring China into revising the terms of other deals elsewhere. Should they fail to agree to new terms, however, then Kinshasa could potentially demand that Beijing sell back its earlier purchased shares in the state-run mining firm, which could also prompt copycat efforts too.

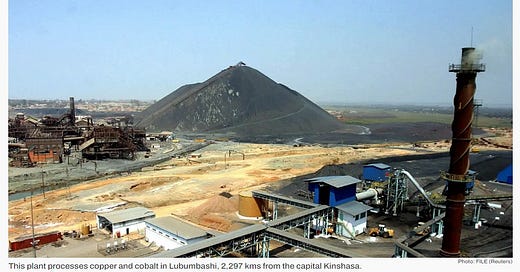

Quartz published a concise report earlier this month about the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s (DRC) audit of a Chinese mining deal from the early aughts and attempts to renegotiate its terms more in Kinshasa’s favor. President Tshisekedi claims that his predecessor Kabila agreed to a massively lopsided arrangement, which he claims Beijing hasn’t even perfectly honored. Accordingly, he wants it to pay more taxes as well as invest more in the DRC’s infrastructure like was initially agreed.

This is a major move for several reasons, the first being that the lion’s share of the world’s cobalt reserves (70%) that are indispensable for the green revolution and modern-day technological devices is located in the DRC, almost all of which (80%) is exported to China according to Quartz’s report. Second, China’s positive reputation across Africa is largely based on the perception that it’s a reliable infrastructure investment partner, but the DRC’s latest claims challenge that notion.

The third and fourth reasons why everyone should pay attention to this concern the potential outcome of their planned negotiations. If they successfully agree to new terms, then this could inspire copycat efforts– including those on false pretexts – for pressuring China into revising the terms of other deals elsewhere. Should they fail to agree to new terms, however, then Kinshasa could potentially demand that Beijing sell back its earlier purchased shares in the DRC’s state-run mining firm.

The final reason why all of this is so important is because either outcome could set a precedent that complicates China’s Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) deals across the Global South that have already been under intense scrutiny since the US declared its trade war against the People’s Republic in 2018. While it’s true that some of the unsavory reports and related investigations into those deals were baseless provocations by the US’ intelligence services, others nevertheless have some substance to them.

This means that they should each be approached on a case-by-case basis exactly as the DRC-Chinese one presently is since it’s inaccurate to paint the scrutiny into every deal with the same brush by either dismissing it all as a foreign intelligence provocation or assuming that every criticism is valid. The outcome of this latest audit and attempted renegotiation might set a standard across the Global South in terms of reshaping perceptions about China for better or for worse depending on the ultimate result.

On the one hand, agreeing to renegotiate the deal’s terms would show flexibility on China’s part and thus counteract the weaponized narrative that it’s laid a series of so-called “debt traps” for its partners through BRI. That said, the cumulative effect of potentially setting into motion a series of seemingly never-ending renegotiations on other deals elsewhere could reduce the profitability of its BRI projects, prolong the time that it takes to recoup its investments, and thus imperial this model in the long run.

On the other hand, however, refusing to renegotiate the deal’s terms would feed into the aforesaid weaponized narrative and risk setting the precedent for Kinshasa to demand that Beijing sell back its earlier purchased shares. Instead of setting into motion a series of seemingly never-ending renegotiations on other deals elsewhere, this could catalyze the process whereby BRI states – irrespective of US influence – consider reappropriating Chinese assets just like the DRC might do.

Both outcomes could have outsized consequences for BRI, but the first-mentioned related to successfully renegotiating the DRC-Chinese deal is preferred when all the risks are considered since it would counteract weaponized narratives while also keeping the BRI model alive for the time being. The second scenario could quickly deal immense strategic damage to Chinese interests, especially if US intelligence weaponizes that process, hence why all efforts should be made to avoid it.

It remains to be seen what will happen, but there’s no question that the DRC’s audit and attempted renegotiation of its mining deal with China is a major move that could have far-reaching economic-strategic reverberations in the New Cold War, particularly with respect to its African front. Observers should closely monitor this process for that reason and remain especially alert for any signs of foreign forces like the US’ intelligence agencies and/or media attempting to influence the outcome.