These ambitious plans are dependent on Djibouti agreeing to a series of Russian-mediated port, mineral, and pipeline deals with Ethiopia and South Sudan.

Russia & South Sudan’s Ambitious Plans

Russia’s TASS just published an interview with South Sudanese Ambassador Chol Tong Mayai Jang, who shared an ambitious vision of bilateral relations that’s worth reading in full here. It’s in Russian, but Google Translate does a decent job conveying what he said for those who don’t know the language. The interview was conducted a little over a month after President Salva Kiir visited his Russian counterpart in late September, thus providing crucial insight into those two’s talks. Here are the top takeaways:

* A deal was reached for Russia to map all of South Sudan’s natural resources for the first time in history

* Russia might also build an oil refinery and even an alternative Red Sea pipeline via Ethiopia-Djibouti

* Negotiations are ongoing, preliminary studies have been carried out, and some financing is secured

* Potential Russian oil investments can lead to investments in other industries too

* Talks are also underway over Russian arms sales and military training programs

* South Sudan hopes that Russia will use its influence at the UNSC to remove the sanctions against it

* It’ll continue pursuing an independent foreign policy despite Western pressure

The context within which their leaders recently met and the South Sudanese envoy just gave his interview to TASS concerns the ongoing instability in (North) Sudan, which surprisingly hasn’t impeded Juba’s oil exports via Port Sudan but still drew attention to how dependent it is on this pipeline. These resource sales constitute 90% of its revenue in what’s the world’s poorest country by GDP per capita and PPP. It’s therefore understandable why South Sudan finally decided to diversify its export routes.

Security & Logistical Obstacles

President Kiir chose Russia as his country’s preferred partner in this respect as proven by the deal to have it map all of his country’s natural resources for the first time in history. OPEC-member South Sudan has the third-largest oil reserves in Sub-Saharan Africa, about 90% of which are believed to be untapped according to reports. Its mineral reserves are also deemed impressive and largely untapped as well, thus making South Sudan a profitable partner for Russia if their resource-related plans succeed.

The two obvious obstacles that’ll need to be surmounted for that to happen are security and logistics, the first of which requires lifting the UNSC arms embargo on South Sudan while the second could be satisfied by Ethiopia. On the topic of sanctions, that global body extended them for another year back in May after Russia abstained. Now that it has the promise of tangible economic stakes in that country, there’s a chance that Moscow might veto next year’s vote in order to secure its potential investments.

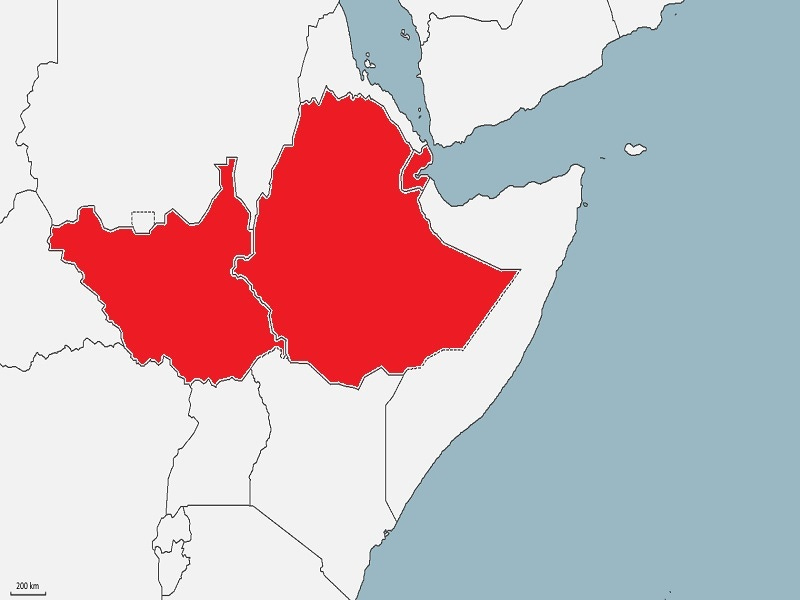

As for logistics, TASS’ interview with the Ethiopian Ambassador to Russia in late September (which can be read in Russian here) revealed that they increased weekly flights from three to four, the aforesaid will soon include cargo, and a deal was reached for Russia to produce Ladas there. Accordingly, it makes sense for neighboring Ethiopia to become Russia’s gateway to South Sudan due to their expanding trade ties, not to mention Juba’s proposal for a Russian-built pipeline through Ethiopia to Djibouti.

Russian-South Sudanese trade and the residual benefit that Ethiopia receives by facilitating this could become even more profitable if Ethiopia successfully diversifies from its dependence on the Port of Djibouti, which charges it an estimated $2 billion a year in port fees. The consequent reduction in costs would make South Sudan’s mineral exports even more competitive on the global market, and this could incentivize Russia to invest in value-added processing plants there and/or in Ethiopia too.

The Ethiopian-Djiboutian Conundrum

The observations shared thus far lead to some intriguing geostrategic insight regarding these three countries’ interests. The Sudanese Conflict that broke out in spring risked imperiling Russia’s access to the neighboring landlocked Central African Republic (CAR) with whom it’s allied and exposed the vulnerability of South Sudan’s oil pipeline upon which most of its revenue is derived. These two then began to realize that they can help each other diversify from their respective dependences on Sudan.

Russia could rely on South Sudan for accessing the CAR while South Sudan could rely on Russia for building an alternative Red Sea pipeline via Ethiopia-Djibouti, but these mutually beneficial plans are admittedly dependent on those two aforementioned countries. Independently of this and without any way of having known about their plans, which were only articulated this weekend in TASS’ interview, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed began exploring ways to diversify from Ethiopia’s dependence on Djibouti.

The West fearmongered that he’s plotting to invade a coastal country even though he explicitly denied this and proposed an exchange whereby Ethiopia would give major stakes in its megaprojects (like the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam [GERD]) to any of them that’s interested in giving it a Red Sea port. Given what the South Sudanese Ambassador to Russia just revealed about those two’s possible pipeline plans, Djibouti might be more likely than before to cut a port deal with Ethiopia in order to facilitate this.

Juba began talking in late August about trucking oil to Djibouti and building a pipeline there via Ethiopia too, but it’s now known from the aforesaid diplomat’s latest interview that Russia is his country’s preferred partner for that second-mentioned initiative. So serious is South Sudan about building this alternative Red Sea pipeline that negotiations with Moscow are currently underway as he confirmed, preliminary studies have already been carried out, and some financing has even been secured.

A Realistic Vision Of The Region’s Future

With this in mind and remembering that Djibouti already serves as the gateway for 95% of Ethiopia’s foreign trade, which China invested in optimizing through the Djibouti-Addis Ababa Railway (DAAR) that serves as its flagship BRI project in the region, Djibouti would do well to reach a deal with all three. If it agrees to PM Abiy’s proposed exchange of a Red Sea port for major stakes in GERD, then bilateral ties could get back on track to the point where they could then seriously discuss Juba’s pipeline plans.

Furthermore, with Russia poised to become a leading investor in South Sudan’s resource industry as was explained, it could consider selling that country’s oil to Djibouti via their proposed pipeline at a privileged rate in exchange for agreeing to facilitate this project. Seeing as how Djibouti imports about $2 billion worth of petroleum each year, which is around the same amount that it charges Ethiopia in port fees, that coastal country could compensate for lost revenue from any port deal via reduced oil costs.

Not only that, but if Russia obtains the rights to extract South Sudanese minerals after completing the recent contract to map the entirety of its natural resources (which could be a reward for vetoing the UNSC sanctions during next year’s vote), then it could offer Djibouti profitable joint investment deals. Likewise, similar such joint Russian-Djiboutian deals could also be reached regarding whatever value-added investments are made in processing these materials in South Sudan, Ethiopia, and/or Djibouti.

Coupled with the major stakes that Djibouti could receive in GERD and possibly other Ethiopian megaprojects and/or newly privatized formerly state-owned companies, whatever reduction in revenue occurs as a result of the proposed port deal could be more than compensated through these means. Its annual petroleum costs could be slashed if Russia agrees to sell it South Sudanese oil at a privileged rate through the proposed pipeline and immense profits could be accrued from joint mineral projects.

Concluding Thoughts

Largely impoverished Djibouti might soon transform into a leading investor in the East African region through the stakes that it could obtain in Ethiopia and South Sudan via Russian-backed deals, the resultant wealth of which could give its people a Gulf-like level of development if properly redistributed. For this mutually beneficial scenario to have any chance of unfolding, Djibouti and/or Ethiopia should request that Russia mediate between them, which could then set the rest of this process into motion.