Any successful Chinese-Bhutanese rapprochement that results in Thimphu ceding Doklam to Beijing would have both military and political consequences for India, but there’s little that Delhi can do to stop it since such a deal would be between sovereign states. In that scenario, Sino-Indo relations would likely deteriorate even further and faster than before if Beijing feels emboldened by its newfound edge over the Siliguri Corridor to redouble its claims to Arunachal Pradesh.

China and Bhutan appear to be on the brink of formally establishing relations after their Foreign Ministers’ meeting in Beijing on Monday. The first said that it’s ready to resolve their long-running border dispute while the second pledged to uphold the one-China principle and praised his host’s Global Development, Security, and Civilization Initiatives. The Chinese-Bhutanese rapprochement is mutually beneficial, but it could have serious implications for India as will be explained in this piece.

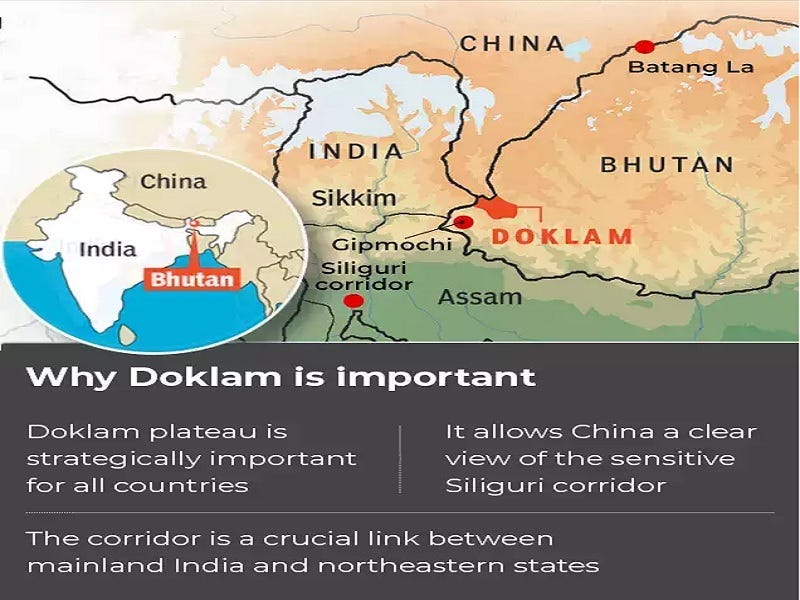

That South Asian Great Power is concerned that any resolution of those two’s border dispute that results in Chinese control over the Doklam Plateau (known as Donglang by Beijing) could give the People’s Republic the military edge over India in the event of another war between them. This slice of territory overlooks the “Siliguri Corridor” connecting “Mainland India” with the “Seven Sisters”, which is only 12-14 miles wide at its narrowest point, hence why it’s nicknamed the “Chicken’s Neck”.

India dispatched troops to Bhutan in summer 2017 to stop China’s construction of a road in this disputed region in accordance with its decades-long defense cooperation with that Kingdom, which objected to what it claimed at the time to be Beijing’s unilateral change of the status quo. Although the crisis ended with mutual de-escalation measures, it set the stage for the lethal Sino-Indo clashes that broke out three years later in the disputed Galwan River Valley, and their ties were never the same after that.

Each consequently regards the other as a rival, which has greatly impeded their cooperation in multipolar fora like BRICS and the SCO despite their shared Russian strategic partner’s best efforts to bridge their differences or at least decelerate the pace at which they continue widening. Another Sino-Indo war therefore can’t be ruled out even though neither wants this to happen, but it could still occur by miscalculation owing to their tense security dilemma that’s only worsened over the past year.

China continues to claim the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh on the basis that it constitutes “South Tibet”, hence Delhi’s concerns that the “Seven Sisters” could once again be the scene of fighting if another war breaks out. In that scenario, China could threaten India’s supply lines through the Siliguri Corridor from Doklam, and it can’t be taken for granted that Bangladesh would allow India transit rights. Even if it did, anti-Indian elements could organize crippling protests and even attack those convoys.

These calculations explain why India militarily intervened in Bhutan’s support to stop the construction of a Chinese road in disputed Doklam over half a decade ago, and it’s precisely because they remain enduring that India is so concerned about the possibility of Bhutan potentially ceding Doklam to China. Considering that China reaffirmed its claims to that region as recently as August after the publication of its annual map, there’s no reason to expect that it’ll drop its request for the plateau’s cession.

In the event that Bhutan swaps that territory with China in exchange for Beijing’s recognition of Thimphu’s sovereignty over other disputed parts of their border, then India would be placed in a difficult position. China’s resultant military edge over the Siliguri Corridor could embolden it to double down on claims to Arunachal Pradesh, which could be pushed to pressure India to drop its own claims elsewhere along their disputed border in exchange for Chinese recognition of India’s control over that state.

The optics of China pressuring India in such a way could also be exploited by the latter’s opposition to portray the BJP as weak ahead of next spring’s elections, especially if they spin Bhutan’s potential cession of Doklam as “the latest domino to fall” after the Maldives just elected a pro-Chinese leader. Coupled with the possibility of the Indian-friendly Bangladeshi government being deposed after next January’s elections, this narrative might become more compelling to a larger number of voters by then.

Viewed from this perspective, any successful Chinese-Bhutanese rapprochement that results in Thimphu ceding Doklam to Beijing would have both military and political consequences for India, but there’s little that Delhi can do to stop it since such a deal would be between sovereign states. In that scenario, Sino-Indo relations would likely deteriorate even further and faster than before if Beijing feels emboldened by its newfound edge over the Siliguri Corridor to redouble its claims to Arunachal Pradesh.

There are three reasons to expect that the People’s Republic might pursue the aforesaid course of action upon obtaining control over Doklam. First, China wants to discredit India’s self-described role as the Voice of the Global South by pressuring developing countries to choose sides between them if another crisis breaks out. Many of them might back Beijing solely because it’s their top trade partner and they don’t want to risk getting on its bad side, which would thus undermine Delhi’s claims of leadership.

The second reason concerns China’s desire to resolve the western half of its border dispute with India on favorable terms to Beijing by leveraging a crisis over Arunachal Pradesh to that end as was explained. China could redouble its claims to that region in order to pressure India into agreeing to a compromise whereby Beijing drops these selfsame claims in exchange for India dropping its own over the Chinese-controlled part of Ladakh that Beijing calls Aksai Chin. This is risky, however, and might backfire.

That brings everything around to the last reason why China might redouble its claims to that region if it obtains control over Doklam since it could be that the People’s Republic wants to shape the narrative that the BJP is weak ahead of next spring’s elections as punishment for refusing to compromise on their dispute. What’s so dangerous about this is that the ruling party might respond more forcefully than China expects, which could lead to another lethal clash or even a war in the worst-case scenario.

Neither China nor India wants to fight one another once again, but the former’s control over Doklam could be perceived by the latter as a game-changer that’ll either force it into compromising against its ruling party’s will or contemplating preemptive military action, thus worsening their security dilemma. China doesn’t want war since that’ll play into the US’ claims that it’s part of a new “axis of evil”, while India can’t rely on US support if need be since it’s already overstretched supporting Ukraine and Israel.

Nevertheless, the further deterioration of their ties that’s expected in the event that China obtains control over Doklam as part of its ongoing rapprochement with Bhutan means that these concerns are disturbingly credible, which is why everyone should closely follow the interplay between those three. Amidst the NATO-Russian proxy war in Ukraine and the latest Israeli-Hamas war, another Sino-Indo war could throw the world into complete chaos, which is why it should be avoided if at all possible.