Russian policymakers would do well to reflect on Medvedev’s advice, which is quite sensible this time.

Former Russian President and incumbent Deputy Chair of the Security Council Dmitry Medvedev lambasted the ambassadors of the EU states in a tweet on Monday for declining Foreign Ministry Sergey Lavrov’s invitation to attend a meeting to discuss foreign meddling in the upcoming elections. This top diplomat revealed that they sent a letter to him two days before the meeting with their decision, which local media cited the EU mission as justifying on the basis of them not wanting to be “lectured”.

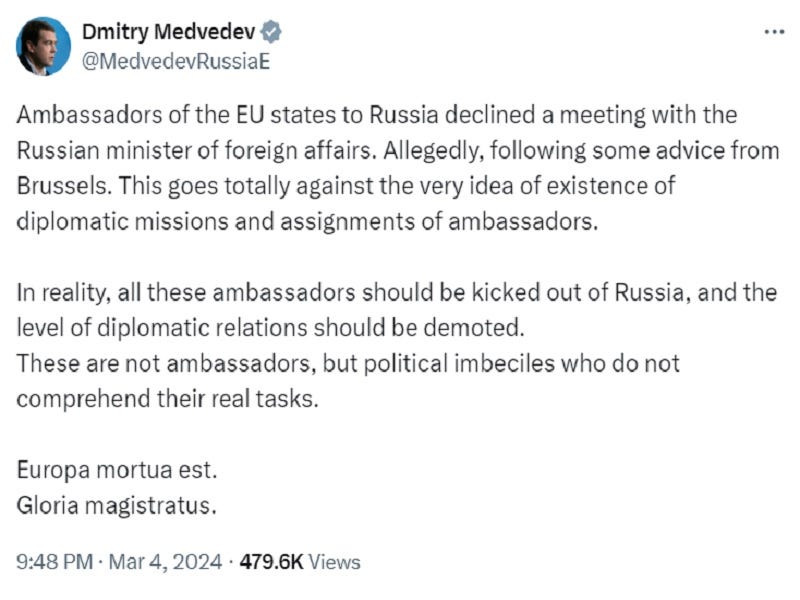

In response, Russia’s previous leader wrote that “This goes totally against the very idea of existence of diplomatic missions and assignments of ambassadors. In reality, all these ambassadors should be kicked out of Russia, and the level of diplomatic relations should be demoted.” While Medvedev has cultivated a reputation as a “hardliner” since the start of the special operation and sometimes shares what can objectively be described as unrealistic proposals, this particular suggestion makes a lot of sense.

After all, Lavrov himself said right after sharing this anecdote, “Can you imagine diplomatic relations with countries whose ambassadors are afraid to attend a meeting with the minister of a country they are serving in?” His remark is all the more relevant when considering that he was preparing to share proof with them of “the mechanisms of interference they use, about projects to support our non-systemic opposition. In general, about what embassies have no right to engage in.”

Russian diplomats have been expelled from the EU en masse on vague espionage pretexts in the past without any proof having been shared with their respective ambassadors of their allegedly illegal activities, yet the EU expects that Moscow won’t touch its own despite the evidence at hand. Even more insulting is the fact that all the EU ambassadors thought that they could snub Russia’s top diplomat without consequence even though they’d surely expel a Russian ambassador if he dared to snub theirs.

That’s not even to mention the fact that the EU is participating in NATO’s proxy war on Russia through Ukraine, including via the dispatch of weapons and even in some cases troops like German Chancellor Olaf Scholz inadvertently revealed last week, which led to an undeclared but thus far limited hot war. For Russia to still retain the same level of diplomatic relations with them requires a saintly level of tolerance for disrespect that risks harming the country’s reputation in the eyes of some foreign supporters.

To be clear, Russia has the right to formulate policy according to whatever its credentialed experts deem necessary to advance its objective national interests, so potentially keeping ties at the same level after this latest provocation should be interpreted as intending (key word) to advance this “greater good”. Nevertheless, there’s also no denying that some of its foreign supporters might perceive it as a sign of weakness, which could lead to them re-evaluating how they assess Russia and its policies.

On the one hand, doing nothing other than summoning those ambassadors for a tongue-lashing (which they might not even show up to receive given the precedent that they just established) or sending a letter of discontent to their embassies could keep dialogue channels open. This would in turn enable them to be relied upon in the event of a crisis or even simply to maintain the low-level of post-sanctions trade between them, both of which do indeed advance some of Russia’s objective national interests.

On the other hand, however, crisis communications could be handled directly between their top diplomatic, military, and/or political representatives if needed without having to go through the ambassadorial level. As for their low-level of post-sanctions trade, this doesn’t require the ambassador’s involvement since it’s conducted via both sides’ respective businesses, which can interact with one another in the event of disputes. Russian interests therefore wouldn’t be harmed if they were expelled.

It's ultimately up to Russian policymakers to decide the best course of action for their country after what just happened, which its foreign supporters should respect even if they don’t agree with it. What’s most important is to understand the imperatives behind whatever policy they promulgate, which can be constructively critiqued but shouldn’t be exploited to discredit the country. Prior to arriving at their decision, policymakers would do well to reflect on Medvedev’s advice, which is quite sensible this time.