Altogether, the pros of Russia’s two lesser-known geo-economic projects in Central Asia far outweigh the cons, which is why the Ministry of Transport is pursuing the International Transport Corridor and Southern Transport Corridor in spite of their respective obstacles.

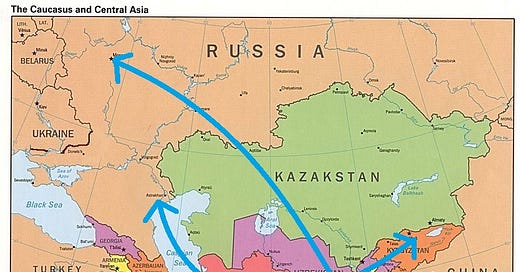

The North-South Transport Corridor (NSTC) figures most prominently in discussions about Russia’s geo-economic projects in Central Asia due to the involvement of India and Iran, but there are two other ones that few are aware of but which the Ministry of Transport just updated everyone about. These are the “International Transport Corridor” (ITC) and the “Southern Transport Corridor” (STC) that’ll crisscross the region upon completion via the North-South and East-West axes respectively.

The first will connect Belarus with Pakistan via Russia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Afghanistan, while the second will connect Russia and Kyrgyzstan (possibly also China as well) via the Caspian Sea, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, the last of which is the indispensable connectivity partner for both. Despite being more ambitious and efficient due to its unimodal nature, the ITC will likely struggle to be completed in full because of continued Pakistani-Taliban tensions, but a workaround exists via the NSTC.

Provided that Iranian-Pakistani relations keep improving after their tit-for-tat strikes in January ended with mutual de-escalation statements and the resumption of diplomatic ties that were briefly broken by Islamabad, then Pakistan can utilize the NSTC to trade with Russia. This route’s Central Asian branch via Turkmenistan can also be used by Pakistan if it takes advantage of that country’s planned infrastructure investments, which its new leader envisages turning his “hermit kingdom” into a regional transport hub.

As for the STC, this clumsy multimodal corridor serves the purpose of preemptively safeguarding from potential Kazakh treachery in the event that Astana capitulates to Western pressure to obstruct Russia’s trade with the other four Central Asian Republics. This scenario is credible enough that Moscow decided to pioneer this trans-Caspian route just in case, which could utilize China’s planned railway with Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan to reduce costs and eventually connect with the People’s Republic as well.

Nevertheless, the comparatively greater costs and longer time that it takes to trade across the Caspian than across Kazakhstan will likely hamper its growth prospects. For that reason, the STC is expected to remain as a backup plan that won’t be employed all that frequently since existing trade across Kazakhstan is much more efficient for all parties. If Astana capitulates to Western pressure, however, then trade across the STC would surge to the benefit of Turkmenistan’s fledgling logistics industry.

Having briefly analyzed the pros and cons of Russia’s two lesser-known geo-economic projects in Central Asia, a few supplementary points become apparent. First, the STC is Russia’s workaround for trading with the rest of the region if Kazakhstan treacherously betrays it and ruins the INC’s prospects, while the NSTC serves a similar purpose for facilitating Pakistan’s trade with Central Asia and Russia if ties with the Taliban remain tense and ruin the INC’s prospects from that direction.

The second point is that Russia can partially rely on Chinese infrastructure in Central Asia just like Pakistan can partially rely on Indian infrastructure in Iran. This insight shows that the use of connectivity infrastructure isn’t exclusively reserved for those who finance, construct, and/or host it but can be employed by anyone just like the Suez and Panama Canals for example. The outcome is that Eurasian integration will proceed apace and accelerate multipolar processes in the supercontinent.

And finally, Russia’s saintly tolerance for Pakistan’s reported arming of Ukraine and dillydallying on years-long strategic energy talks could be partially explained by Moscow wanting to tap into its massive market potential via the INC/NSTC upon the stabilization of that country’s crises. That’s why it turns a blind eye to both as opposed to giving Islamabad a tongue-lashing for the first and de facto freezing the aforesaid talks in order to invest its limited resources in negotiating deals with more interested partners instead.

Altogether, the pros of Russia’s two lesser-known geo-economic projects in Central Asia far outweigh the cons, which is why the Ministry of Transport is pursuing them in spite of their respective obstacles. Both are still in their infancy and will therefore take some time to fully enter into operation, but it’ll be well worth it once they’re completed since they’ll accelerate multipolar processes. The supercontinent will then continue its geo-economic integration and become more difficult for the West to divide-and-rule.