Regardless of however one feels about China and Pakistan’s problems with India, it’s in their collective interests that the latter plays a much greater role in Afghanistan via the SCO-centric Quartet. In pursuit of the greater multipolar good, hopefully those two will welcome it to the club after Lavrov’s invite.

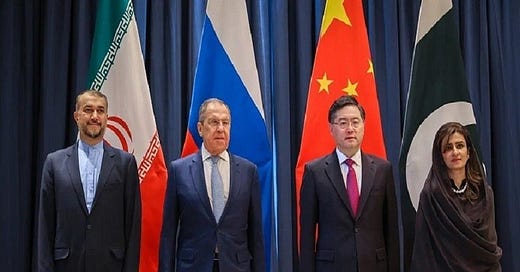

Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov told reporters during a press conference at the UN on Tuesday that his country invited India to join the Afghan Quartet that’s presently comprised of itself, China, Iran, and Pakistan. In his words, “We want this Quintet to be constituted as something of a core for the format of neighbouring states”, which reveals the larger strategic intention behind this move. Basically, Russia envisages this platform bringing the largest SCO member states together to resolve regional issues.

From this observation, it can be intuited that the driving principle is “Eurasian solutions to Eurasian problems”, which is spiritually similar to the African Union’s approach of “African solutions to African problem”. The challenge, however, is for China and Pakistan to agree with Russia’s request for India’s inclusion into this platform. Iran is closely aligned with India so its support is taken for granted, but those other two have tense ties with it, especially China nowadays.

At the same time, they’re unlikely to go too far in impeding India’s participation since that would signal that their leaderships are letting bilateral disputes get in the way of multilateral cooperation, thus discrediting their publicly proclaimed multipolar goals. Nevertheless, they might twist Lavrov’s description of the Quartet’s members as “neighbouring states” to argue against India playing a role in their group on the grounds that it doesn’t exert writ over any Afghan-adjacent territory.

Moscow wholeheartedly supports Delhi’s stance towards the unresolved Kashmir Conflict but also recognizes the status quo too, though the latter doesn’t influence its official policy formulation otherwise Lavrov wouldn’t have indirectly reaffirmed India’s claims to the entirety of that disputed region. China and Pakistan, meanwhile, take the opposite approach of actively opposing India’s claims. Guided by their official policies, one or both might accordingly argue that India isn’t eligible to join the Quartet.

Should that happen, then Russia would question their commitment to multipolarity after they let bilateral disputes impede multilateral cooperation. Moscow might also wonder whether they’re tacitly opposed to its own participation in that group since Russia doesn’t abut Afghanistan at all. If no such obstacle is put in India’s way, then it could begin taking part in this platform right away, which would strengthen its stakes in the Eurasian Heartland and thus maintain its balanced foreign policy.

Regardless of however one feels about China and Pakistan’s problems with India, it’s in their collective interests that the latter plays a much greater role in Afghanistan via the SCO-centric Quartet, which could then evolve into the Quintet or rebrand in some other way. It’s already the world’s most populous country, its fifth largest economy that’s on track to become its third largest by the end of the decade, and aspires to informally lead the Global South amidst the impending trifurcation of International Relations.

The Quartet’s socio-economic and political engagement with Afghanistan will therefore always remain suboptimal so long as India remains outside of this platform, hence why this should be remedied as soon as possible. That Great Power requires a leadership role in Eurasia commensurate with its rising status in global affairs, with it being natural that India assumes this position via the SCO-centric Quartet. In pursuit of the greater multipolar good, China and Pakistan should welcome India to the club after Lavrov’s invite.