Why Are Abkhazians Protesting Against An Investment Deal With Their Russian Benefactor?

Abkhazia’s reputation in Russians’ eyes has been damaged by the latest unrest.

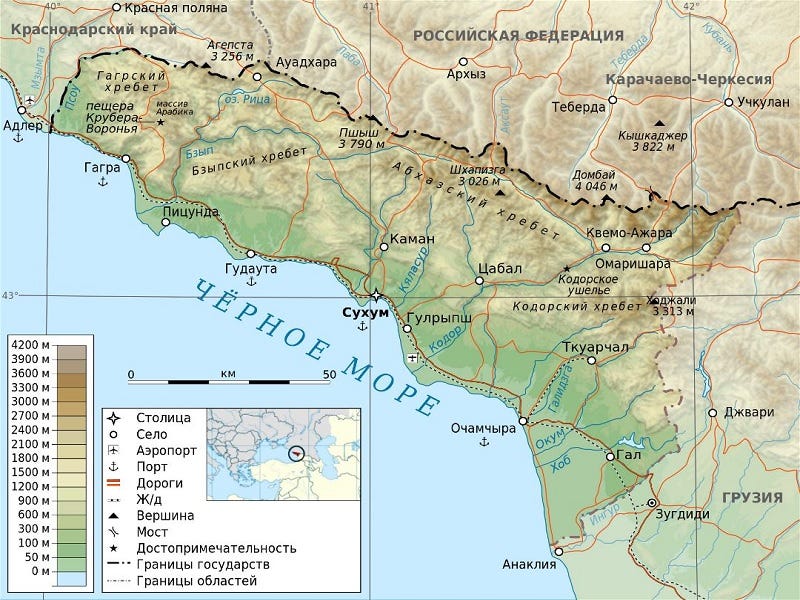

Abkhazia is considered a Russian ally after Moscow recognized its independence in 2008 following that August’s five-day war with Georgia, yet a critical mass of its people is now protesting against an investment deal with their benefactor, even going as far as to storm and occupy the local parliament. Outside observers might therefore assume that this is an anti-Russian revolt, whether a naturally occurring one or a foreign-orchestrated Color Revolution, but the situation is more complicated.

The demonstrators insist that they’re not against Russia and some have even flown Russian flags during their protests, but they also claim that the terms of the proposed investment deal might only benefit wealthy oligarchs and thus come at the expense of average Abkhazians. These people have a very strong sense of nationalism which began to manifest itself during the early Soviet period, exploded into a brutal war with Georgia shortly after the USSR’s dissolution, and is now once again making itself known.

This is typical of the Caucasus region, whose people on both sides of that mountain range are stereotyped as being fiery and hot-headed, which has historically led to trouble for Russia. Sometimes their perception of contemporary issues, regardless of whether this accurately reflects objective reality, leads to them forgetting everything that Russia has done for them in the past. Such is the case with the Abkhazians who are now taking Russia’s patronage of their largely unrecognized country for granted.

The only reason why their polity has continued to survive from the early 1990s till today is due to the presence of Russian forces there, first as peacekeepers in agreement with Georgia and then as allies per a bilateral deal after Moscow recognized its independence. Many ethnic Abkhazians, who constitute around half of the population, nowadays hold Russian citizenship. The Kremlin also funds over one-third of its ally’s budget, supports its armed forces, and pays for many of its people’s pensions too.

It therefore isn’t an exaggeration to say that Russia is responsible for Abkhazia’s political existence to this day since it couldn’t defend itself from NATO-backed Georgia nor develop without Moscow’s assistance. The Kremlin’s interests in Abkhazia are military and political in the sense of preventing NATO from threatening Sochi via Georgia and fulfilling its promise to protect this polity. Abandoning Abkhazia would engender serious national security threats and irreparably harm Russia’s reputation as a reliable ally.

Nevertheless, Russia also envisages Abkhazia economically developing in order to preemptively avert poverty-inspired unrest there that could pose latent security challenges with time, yet its financial generosity all these decades hasn’t led to any serious improvements in those people’s living standards. Abkhazia is still run-down and underdeveloped, obviously due to corruption, hence why Russia now feels the need to directly invest there in order to bring about long-overdue and much-needed development.

For that to happen, however, there must be legal guarantees for its investors. Tourism is essential to its economy is to also follows that this would be the most attractive industry for Russians to invest in. Accordingly, Abkhazians expected that the proposed investment deal’s passage would result in their neighbor buying more real estate, which some of them feared might only perpetuate endemic corruption and disadvantage the locals. These perceptions are behind the ongoing unrest.

The security services also treated some of the rowdier demonstrators heavy-handedly, and regardless of whether one believes that this was justified considering that they were storming government buildings, it served to fuel even more unrest and radicalize the protesters into demanding regime change. Something similar took place in summer 2014 over related nationalist concerns, which led to the incumbent’s resignation and early elections, so what’s happening right now isn’t unprecedented.

With this in mind, it would be a mistake to overreact by labeling the protesters as enemies of the state or of Russia, even though their tactic of weaponizing protests could be criticized. Doing so might radicalize them even further and lead to them rationalizing the use of more violent methods if they consequently fear persecution after the unrest finally ends if they fail. That could lead to a full-fledged security crisis that creates the West’s long-desired “second front” for distracting Rusia from its special operation.

To be sure, the Abkhazian government and the Russian one could have done more in recent months to explain why this proposed investment deal is needed and how it’ll improve average people’s lives with time upon its promulgation, which could have prevented misperceptions from proliferating. Both will presumably learn from their shortcomings and apply these lessons in the future, but for now, the priority is stabilizing the situation so as to prevent the abovementioned worst-case scenario from materializing.

This can be done through either a soft or hard approach. The first involves complying with the protesters’ demands to withdraw the proposed investment deal and then holding early elections after the president’s resignation. Anyone who continues violating the law by occupying government buildings would then be subject to a crackdown. This solution doesn’t solve Abkhazia’s systemic problems, however, it only pushes back the requisite reforms. Another political crisis might therefore be inevitable.

The second approach involves cracking down on lawbreakers right now, beginning by rounding up the ringleaders and then only later arresting those who still continue to disrupt the state’s functioning. Parliament could then pass the investment deal, but only if the aforesaid crackdown doesn’t backfire by provoking more unrest, which might then take overtly anti-Russian dimensions if the Kremlin is blamed for any casualties. This could result in the self-fulfilling prophecy of opening up a “second front” of sorts.

Regardless of whatever happens, Abkhazia’s reputation in Russians’ eyes has already been damaged. Only the boldest investors would pour money into there since most might now expect that their projects could be attacked by misguided nationalists. Average Russians might also fear vacationing there if ultra-nationalist sentiment rises and speculation abounds that radical Abkhazians might be planning another pogrom like the one that they were accused of carrying out against Georgians in September 1993.

As for the Russian state, it now knows how ungrateful many Abkhazians are for its generous aid seeing as how quickly a critical mass of them assembled to protest against the proposed investment deal. That was certainly a surprise since Russian officials would have advised their Abkhazian counterparts to hold off on tabling this legislation until public opinion could be reshaped had they been aware of this. Russia will still support Abkhazia regardless of however this crisis is resolved, but its approach might change.

Instead of blindly backing it like before, all forms of aid other than the pensions that it pays to its nationals there might be scaled back, and what remains might only be extended if the authorities agree to be fully transparent with the public about how it’ll be spent. Other forms of support in the energy and military domains could also be provided according to market conditions or in exchange for something tangible from now on. The only ones who’d be to blame for this are misguided Abkhazian nationalists.

I was in Abkhazia in mid-October and spoke to a number of people there, including Sergei Garmonin, the last independent publisher in Abkhazia. At the center of the protests is a quasi-invisible factor, namely the globally unique fact that private land ownership is not possible in Abkhazia. All land belongs to the state, which allocates it to its citizens on application, in the cities for a rent, in the countryside free of charge. What is built on the land belongs to the builders and can also be sold, but the land itself cannot. And to be allowed to build, you have to be an Abkhazian citizen. The traditional attitude towards private property is also reflected in the fact that there is no word for “money” in the Abkhazian language.

This rule - no private ownership of land - is apparently supported by the vast majority of Abkhazians, as I was told. It is also explicitly seen as a guarantee that Abkhazia will not fall into the hands of Russian oligarchs. This is because the country was something of a Monaco of the East during the Soviet era. Many magnificent buildings have since fallen into ruin. With a little money - which the Abkhazians don't have - the past splendor could be restored. As a rich Russian, I would also keep an eye on the beautiful plots of land in the subtropical climate.

Another remarkable detail about Abkhazia is the fact that there is no post. So you never find bills in your letterbox and you can't send off a tax return either. Many state institutions in Abkhazia are based on personal relationships. Having already entered the country I experienced this when I tried to get a visa with the help of Sergei Garmonin. You first have to transfer 400 roubles through a bank to the passport office which doesn’t accept cash or electronic payments at the counter. Then you go to the passport office with the proof of payment and receive your visa within a few minutes and without any further paperwork.

Now two banks didn't want to accept the transfer worth four euros, for God knows what reasons. Then Sergei called a friend - I think it was a former foreign minister. He appeared within five minutes and told the friendly ladies at the counter to make the transaction, which they did. When I asked Sergei why it had suddenly worked, he replied. “My friend was someone they knew.”

It is clear that a state system that is so characterized by personal relationships is relatively lean, but on the other hand it is also very susceptible to corruption. And since the state or its representatives grant land rights, a lot of roubles can quickly be at stake. Perhaps the fact that small Abkhazia has a professional parliament of 35 members that meets daily and also allocates land rights also plays a role. The parliamentarians like to be among themselves. The growing distance between the people and the parliament is symbolized by the high fence that was recently erected around the parliament building.

This parliament now wants to make it much easier for Russian investors to do business in Abkhazia. Not least, these investors are to be allowed to use the land in Abkhazia as collateral for bank loans, which not even Abkhazians can do, as private land ownership is not possible.

It seems quite plausible to me that the Abkhazians are rebelling against this. And there would certainly be opportunities to use Abkhazia's great potential not only for the benefit of Russian capital, but also for the general benefit of the country and its people.

Your post has some omissions. The russian minister of economy wants to deregulate the housing market in Abkhazia. He probably believes that free market is a good thing without understanding the consequences.

Abkhazia is a special region, with a special history and identity.

Abkhazia is poor but it's a turistic area.

Allowing non-residents to buy properties there will not improve the local economy, and will price residents out of the housing market.

So, Abkhazians are totally right to complain about this.