The sequence of events that would have to transpire in order to turn this into a reality are that: the next NATO leader and his team end up being hawkish on this issue; Polish policymakers overcome their differences and agree that it’s worth the risks; and the US gives them the greenlight.

Polish Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski told the Financial Times in an interview earlier this week that “Membership in Nato does not trump each country’s responsibility for the protection of its own airspace — it’s our own constitutional duty. I’m personally of the view that, when hostile missiles are on course of entering our airspace, it would be legitimate self-defence [to strike them] because once they do cross into our airspace, the risk of debris injuring someone is significant.”

Foreign Ministry spokesman Pawel Wronski clarified that these was Sikorski’s own personal views and don’t reflect Poland’s official ones, elaborating that “If we have the capability and Ukraine agrees, then we should consider it. But ultimately, this is the minister's personal opinion.” Nevertheless, their comments still suggested that this scenario might once again be in the cards under certain conditions despite having earlier been rebuffed by the US, UK, and NATO. Here are three background briefings:

* 17 April: “It Would Be Surprising If Polish Patriot Systems Were Used To Protect Western Ukraine”

* 18 July: “Ukraine Likely Feels Jaded After NATO Said That It Won’t Allow Poland To Intercept Russian Missiles”

* 30 August: “Poland Finally Maxed Out Its Military Support For Ukraine”

The last of these three included Zelensky’s most recent demand at the time to shoot down Russian missiles over Ukraine. He said that “We have talked a lot about this and we need, as I understand it, the support of several countries. Poland ... hesitates to be alone with this decision. It wants the support of other countries in NATO. I think this would lead to a positive decision by Romania.” That same analysis also cited Defense Minister Wladyslaw Kosiniak-Kamysz’s response to him too.

In his words, “No country will make such decisions individually. I have not seen any supporters of making this decision in NATO. I am not surprised that President Zelensky will appeal for this because this is his role. But our role is to make decisions in line with the interests of the Polish state. And that is what we are making today.” This aligns with what outgoing NATO Deputy Secretary Mircea Geona told the Financial Times in response to Sikorski’s opinion on this issue.

That Romanian official said that “We have to do whatever we can to help Ukraine and do whatever we can to avoid escalation. And this is where the line of Nato is consistent from the very beginning of the war. Of course we respect every ally’s sovereign right to deliver national security. But within Nato, we always consult before going into something that could have consequences on all of us — and our Polish allies have always been impeccable in consulting inside the alliance.”

This context confirms that Sikorski was only speaking in a personal capacity and that neither the Polish state as a whole nor Romania (which Zelensky suggested could take part in this as well) is seriously interested in shooting down Russian missiles over Ukraine. The question therefore arises about what he thought that he’d achieve by sharing his opinion on this seeing as how it’s unlikely to lead to anything. Several explanations exist for why he did so.

The first is that he wanted to placate Ukraine after Poland failed to fulfill its pledge from this summer’s security pact to “continue their bilateral dialogue and dialogues with other partners, aimed at examining rationale and feasibility of possible intercepting in Ukraine’s airspace missiles and UAVs fired in the direction of territory of Poland, following necessary procedures agreed by the States and organisations involved.” Talking tough on this issue shows Kiev that there are still policymakers in favor of this scenario.

The second is he’s trying to craft the narrative that some in Poland want to do more to help Ukraine win but are being held back by rival policymakers and the West, which might be designed to deflect criticism from Warsaw in the event that Kiev suffers major battleground setbacks in the near future. Sikorski has deep lifelong ties to the Anglo-American Axis and is a proud Ukrainophile so he might seriously believe that it serves Polish interests to exaggerate its willingness to do everything possible for Kiev.

And finally, the last explanation – none of which are mutually exclusive – is that he’s presenting himself as the public face of much more powerful forces that plan to vigorously lobby for this scenario upon former Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte becoming NATO’s next Secretary-General next month. While the logic behind the bloc’s reluctance to approve such an unprecedented escalation in their proxy war with Russia will remain, some incoming officials might be even more hawkish than their predecessors.

Observers likely don’t have to worry about NATO approving Sikorski’s proposal for Poland shooting down Russian missiles over Ukraine this month since Jens Stoltenberg (who’s against this) is still in office, but they’d do well to closely monitor all the related remarks of his successor and the latter’s team. Even if they openly advocate for that happening, Poland will still informally require US approval before going through with this, and that’s presupposing that its policymakers finally get on the same page about it.

The sequence of events that would therefore have to transpire in order to turn this into a reality are that: Rutte and his team end up being hawkish on this issue; Polish policymakers overcome their differences and agree that it’s worth the risks; and the US gives them the greenlight. Even if the first two are in place, nothing will probably happen unless the third is as well since Poland is unlikely to feel comfortable acting unilaterally without knowing for sure that the US has its back.

It’s here where the on-the-ground dynamics of the Ukrainian Conflict and the outcome of the US’ presidential elections could play decisive roles in determining whether or not the US gets on board. As for the first, the possibility of a Russian military breakthrough upon its capture of Pokrovsk could prompt Western panic and make this scenario appear more attractive to decisionmakers. It could also, however, make them even more reluctant to escalate and risk a hot war with Russia by miscalculation.

Regarding the second, the Democrats might want to sabotage Trump’s promised peace efforts if he wins by carrying out the aforementioned escalation as vengeance irrespective of the conflict’s on-the-ground dynamics. If he loses and there isn’t a Russian military breakthrough, then the Democrats might stay the course with their policy of gradual escalations instead of resorting to a sudden radical one like approving the proposal of Poland shooting down Russian missiles over Ukraine with all the risks that it could entail.

Seeing as how these supplementary variables are beyond observers’ control, as is the sequence of events was detailed several paragraphs before, nobody can say with confidence that the US will ultimately approve Sikorski’s proposal. Like was written earlier, the logic behind their reluctance to escalate in such an unprecedented way will remain, and more Russian on-the-ground gains could reinforce this sentiment. The coming months will show whether these calculations change or not.

Any time you read that an escalation is "under consideration", the decision has already been made and the escalation begun. Any "debate" is for public consumption.

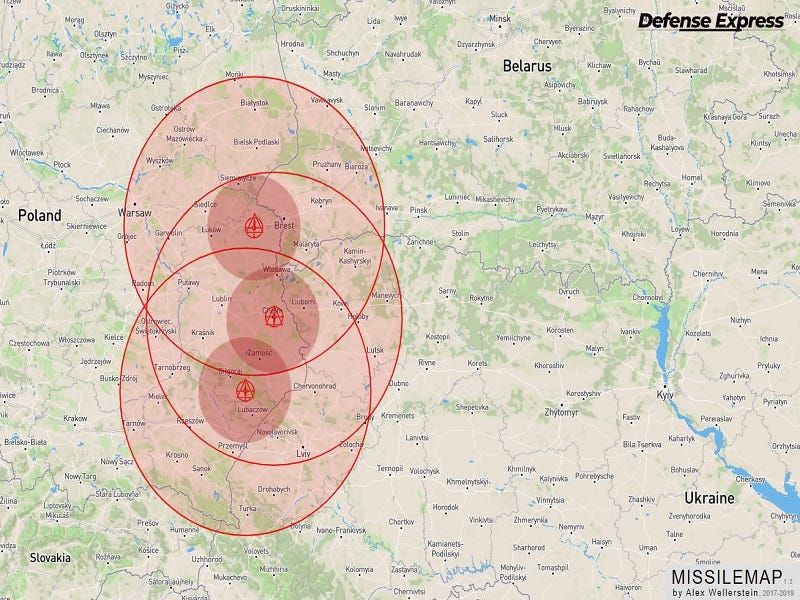

I note that Russia is testing Poland's resolve with missile attacks on Lviv.

The Ukraine have had little luck taking down these missiles with their Western weapons, good luck to Poland in trying same.

You know what they say about the definition of a Moron.